Love and War on the Jewish Riviera

When Long Beach,NY and Miami Beach,FL were Jewish, my grandparents' lives kept intersecting.

A lifetime ago, when I worked at the Tank, I began researching a book about the generational implications of policy, using my Jewish family’s story as a case study. My team had just released a report revealing the anti-Black and anti-Latino racism baked into the process for applying for unemployment insurance. I knew my own family’s story had been shaped by restricted hotels and towns, college quotas … what other policies, either whispered or government-approved, were anti-Jewish?

Then, after the Tank told me I was ethnically White, I did what researchers do. BRB, I thought. Lemme research and write this book proving you wrong.

Research always takes you in unexpected directions. Initially, I wanted to contrast my family’s immigration and Americanization experience with that of a family who immigrated in the 1980s from Latin America. The Right was demonizing refugees, I was at a Left-wing Tank, and this seemed like an idea the Tank would support.

But once I started piecing together my family’s story, I quickly saw that rather than being a factor in my story, the policies, whispered gentlemen’s agreements, closed doors and outright exclusion were the factor.

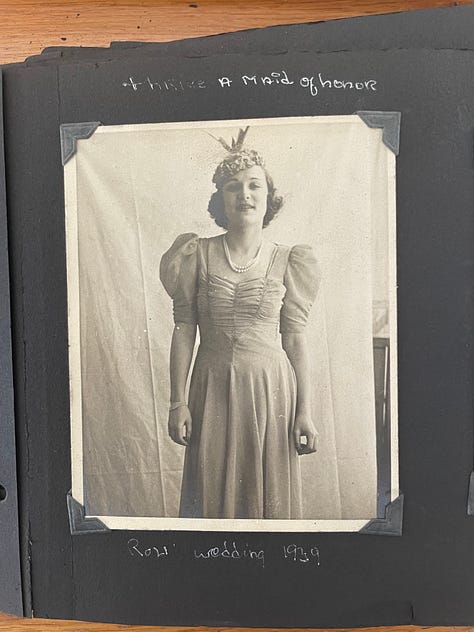

I always planned to center my foremothers in the story, because I know so few Jewish women’s stories. The portrayals of Jewish women in the media bore no resemblance to the women in my family. Almost all my foremothers were the family’s primary wage earner, though no one dared speak that truth aloud. No one maxed out credit cards. Everyone scrimped and saved. And, the women all shaped their family’s Jewish practices, deciding how best to raise Jewish children in a world that wanted to do them harm.

So began by researching my great-grandmother Chava Lutsky Schank’s story, envisioning writing scenes of her climbing aboard a horse-drawn carriage at 16 for the trip from her shtetl to the teeming city of Pinsk, being groped on the ship crossing (a common occurrence for women traveling alone), and giving birth to my grandfather in a filthy tenement on the Lower East Side.

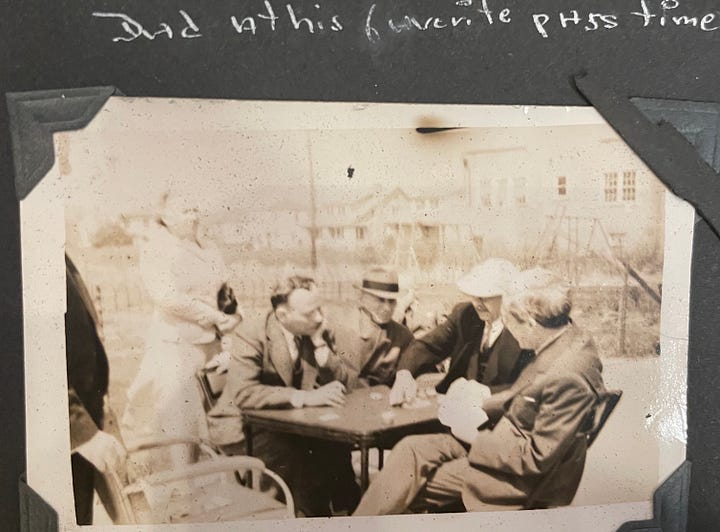

I chose Chava because in family stories, she sounded awesome. She ran the boarding house in the Borscht Belt that turned into a hotel in Lakewood, NJ, played poker with the men, smoked, gambled, and took mysterious solo trips to Cuba. She read Hollywood tabloids and joked that JFK could “park his shoes under my bed anytime.” She’d been arrested and briefly jailed for allowing gambling at her hotel. Who was this woman?

But as I researched Chava’s life, I couldn’t help but notice how dramatically it contrasted that of my grandmother, Margie Rosenberg, with whom I’d been close as a child and young adult. So I looked into Margie’s family’s story. Turns out, Ashkenazi Jewish refugees to America were not all the same.

In the Russian Empire, where Chava’s family likely lived for centuries, Jews were repeatedly brutalized in pogroms, unable to own land, confined to the Pale of Settlement1, and conscripted into the army as young as nine. But in Hungary, where Margie’s family had lived for generations, Jews were able to own land for a period of time. When they were allowed to serve in the Hungarian army, it was considered a privilege, and Jews lined up to enlist2.

Margie lived a life of privilege in Manhattan and Brooklyn, traveling back and forth to Hungary frequently to visit family.

Meanwhile, Chava lived in a farmhouse with an ever-increasing number of relatives fleeing Tzar Nicholas’ bloody regime. Margie’s father was the only member of his enormous family to come to America, where he founded a successful business importing beads from Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Germany.

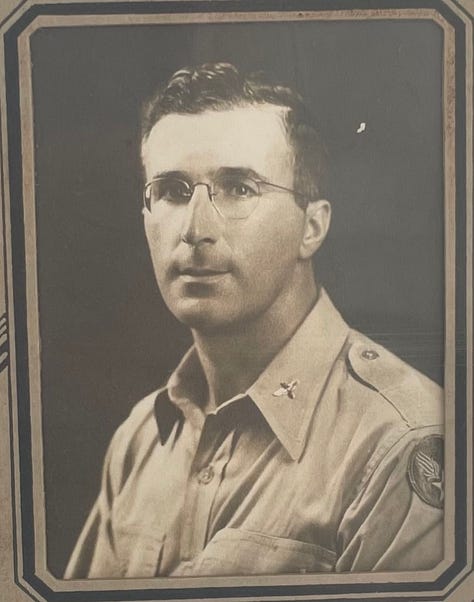

In 1941, Margie was vacationing with family and friends in Miami Beach3, and apparently having the time of her life. While at Hialeah Racetrack with friends, a handsome GI tried to pick her up. Mac Schank, Chava’s son, was on leave from his posting at the Miami Army Airfield. He was cute in a sort-of Jewish Talmud chakhem way, and had an impressive quota-era law degree from Columbia University. That night they went out to the White House hotel, followed by a date to the Orange Bowl. And then Margie returned to New York and Mac to the Miami Airfield.

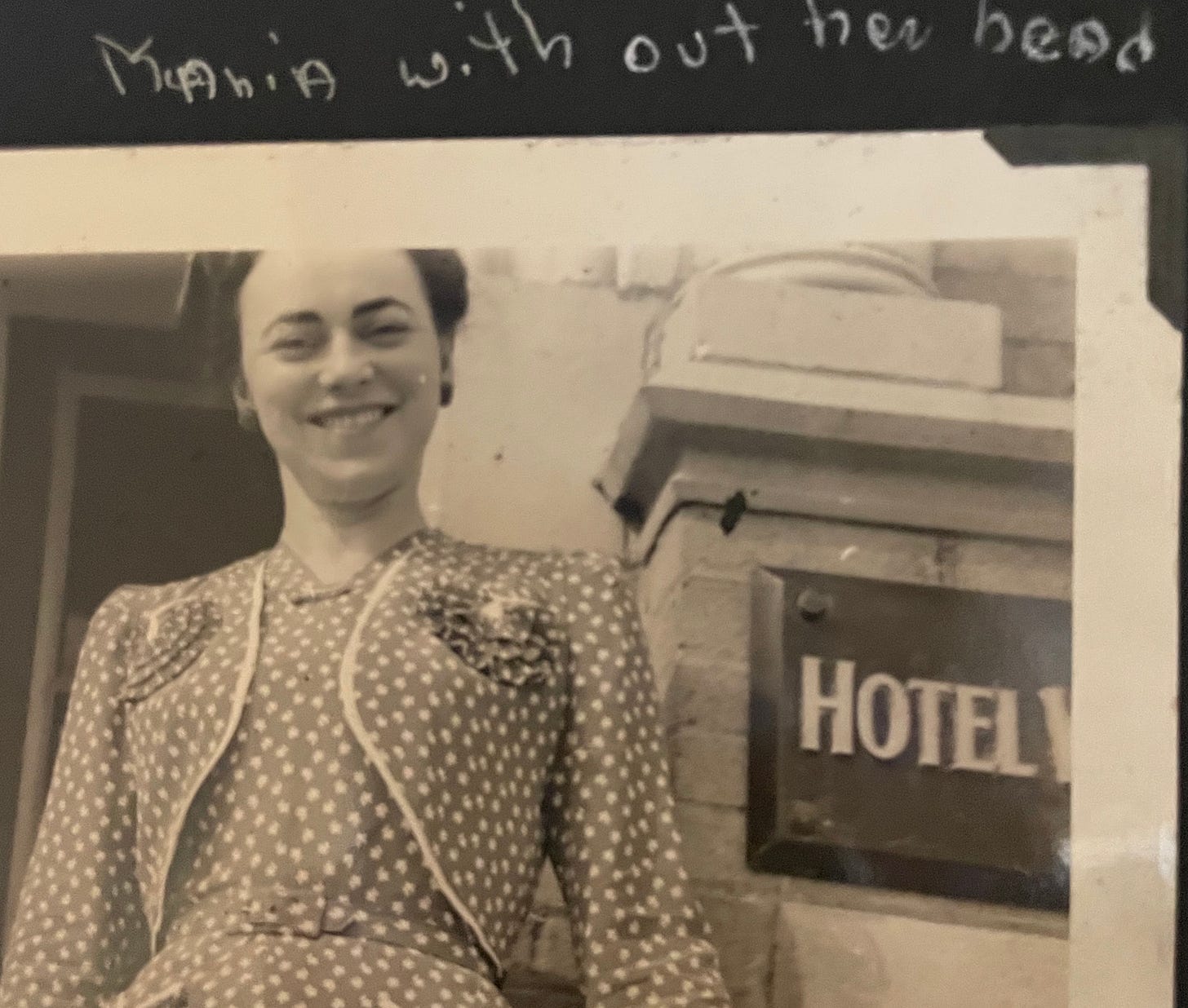

Earlier that year, Margie spent Passover at the Hotel Winkler with her family, as they did every year, because her mother said keeping their Bensonhurst apartment both kashrut and chametz-free would give her a nervous breakdown. Instead, they decamped to the Winkler in Long Beach, Long Island, along with a hotel’s worth of other Hungarian Jews.

Long Beach, just five miles past the Queens border, was restricted to a White, Protestant summer resort crowd until the early 1920s3. Once the restrictions eased, Jews established a synagogue, then kosher hotels, and eventually a Jewish holiday and summer alternative to the Catskills or the Jersey Shore4.

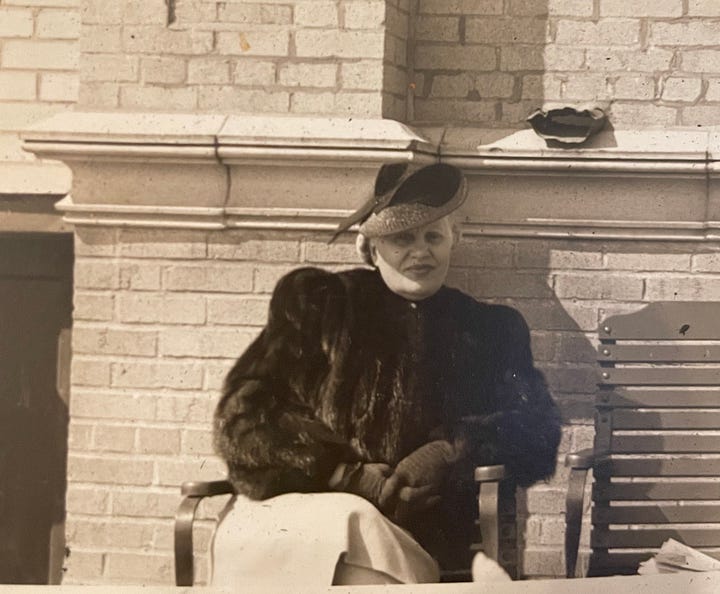

In 1941, at 25, Margie must have been bored out of her mind in Long Beach at Passover. Her father played mahjong with friends. Her mother sat out front, cold and unhappy in fur and gloves.

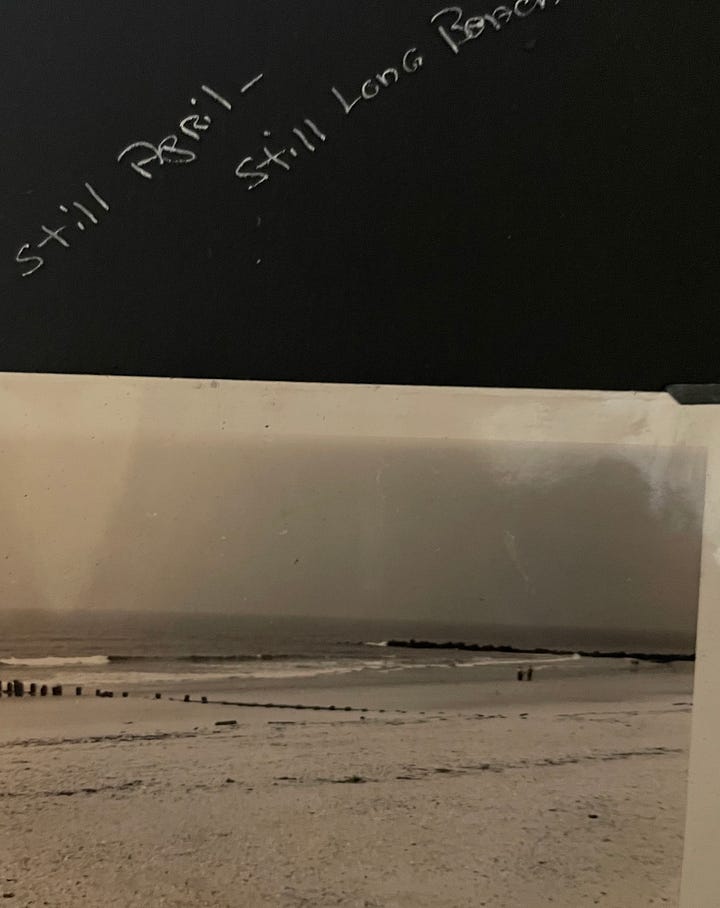

And Margie took a walk on the empty April beach. Multiple long walks. With her treasured camera, a gift from Daddy.

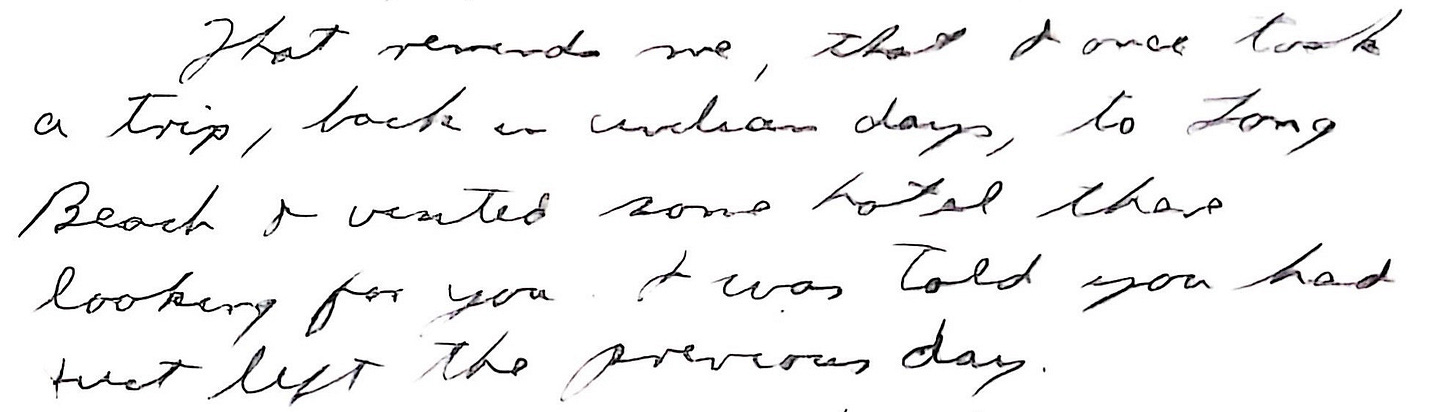

Margie must have mentioned the Winkler to Mac on their date. Meanwhile, Mac hadn’t been able to get Margie out of his head. In ‘42 or ‘43, while home on leave in Lakewood, NJ, Mac drove 100 miles to the Hotel Winkler looking for Margie, only to learn he’d just missed her.

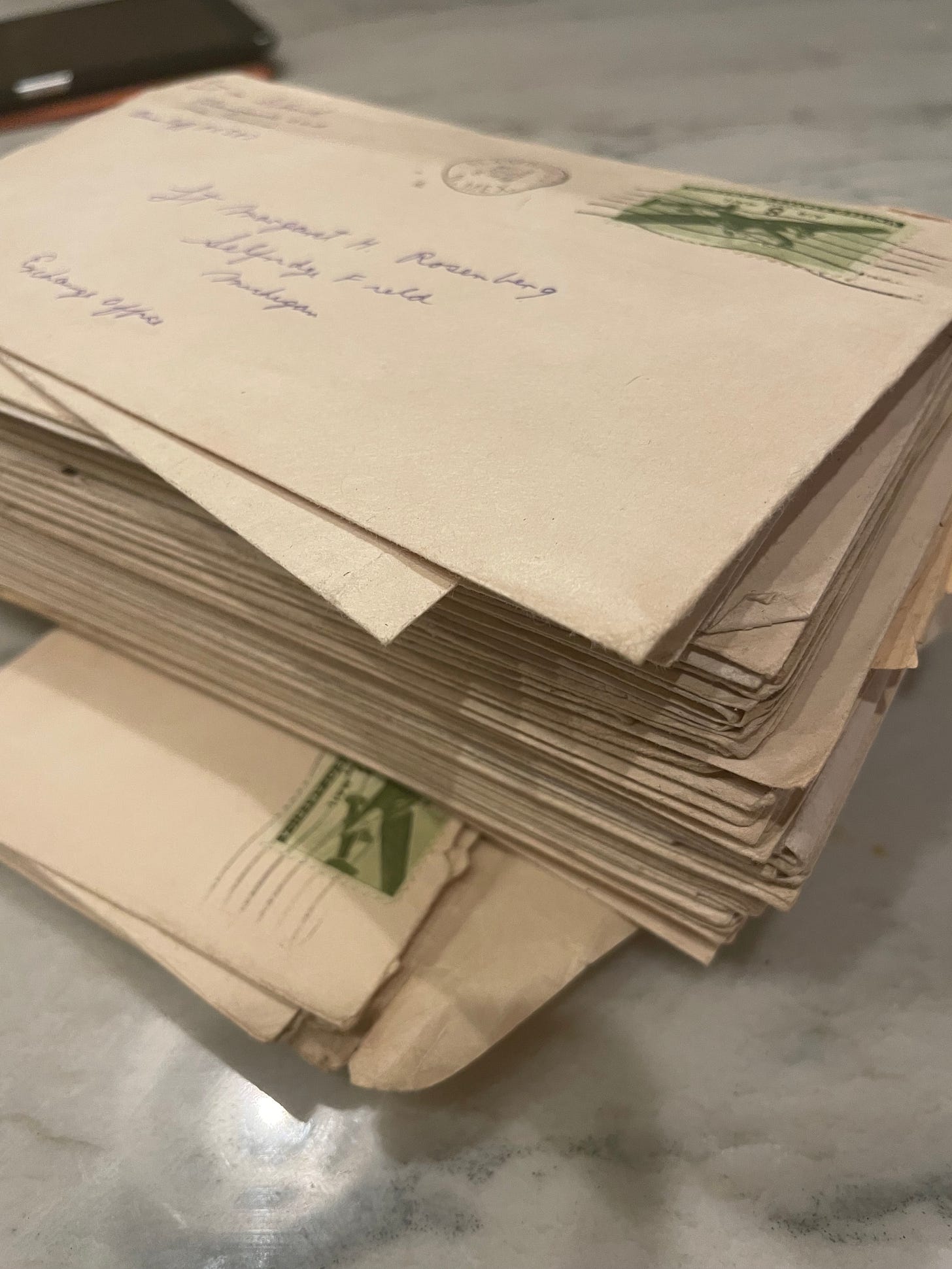

In January, 1944, Mac sent Margie a letter at her parents’ apartment in Bensonhurst. She wrote back that she, too, was now in the military. By 1946, after two years of correspondence, followed by two weddings, they were back in Margie’s parents’ Bensonhurst, this time with a new baby — my father. Margie saved every one of Mac’s letters, in chronological order. He saved none of hers. (We also realized, after he died, that he owned nothing except a watch, binoculars for the race track, and multiple Kangol hats.) I like to think she was saving them for me.

I’d long heard about the Winkler, where my father and his cousins suffered through endless annual Orthodox seders, but also where they spent time together as a family. I knew Long Beach was basically Queens, and not far from where I live, but I’d never even thought to visit. Last weekend it hit 80 degrees, and after looking again at Margie’s pictures, I wondered if the beach looked the same. Maybe I could even find whatever the Winkler Hotel was now? So I went. For the book. It’s taken such a long and winding route, who knew what this trip might turn up?

Today, Long Beach has a fading Jewish community, beautiful 1930s architecture, year-round residents and a yoga studio. The houses are big, expensive, and tightly packed together. The boardwalk is beautiful, and the sand is pillowy, unlike the dirt granules of Coney Island or the Jersey Shore.

As my husband and I walked around, then ate lunch at what had clearly once been a kosher deli, it was hard not to feel a sort of sadness — not quite melancholia or nostalgia — but an odd proximity to a vanished past. I saw ghosts in the diner, and asked our waiter where the perfectly sour and crisp pickles came from. He did not say Delancey Street. “The pickle guy?” he shrugged.

But what I also saw, in Long Beach, was a fleeting moment in time — when Jews lived fully Jewish lives in America without fear, still connected to their families in Europe, but excited about all the possibilities their new country held. I’m glad my family had the chance to live their American dream for a time, no matter how fleeting. How fortunate they could experience the freedom to be Jews without the fear of imminent death, relentless poverty, or dehumanization. Before they learned what was happening in Europe, and knew they could never go home again.

As a writer, it’s always worth taking the time to rub shoulders with the past. I get Long Beach and the Winkler in a way I didn’t before. I feel closer than ever to Margie, though she’ll have been gone 20 years ago this December. Just six weeks after my son was born. In accordance with Jewish tradition, we named him after Mac. Three years later, we named my daughter after Margie.

“I’m sorry you were so bored here,” I said to Margie’s ghost at the beach. “But generally, it worked out okay for you in the end, and I love you.”

Jews in the Russian Empire were required to live in the Pale of Settlement, which stretched across modern-day Poland, Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine.

One of Margie’s Rosenberg uncles died in World War I, fighting for Hungary. Another, Desko Roth, served in the Hungarian Army only to die in Auschwitz.

https://www.liherald.com/longbeach/stories/temple-israel-100-year-historic-landmark,210133

Many towns along the Jersey Shore did not allow Jews.

Hana—After hearing bits and pieces about your grandmothers, I’m really happy to read this fuller version. More, please!

Friends here have invited me to their seder. May I take copies for them and the other guests?

My contribution to the meal: some KP wine. I was able to find a KP St. Emilion (at kosherwines.com)! St. E is my favorite Bordeaux, so I’m really excited to be able to do this.

Wishing you and your family a great holiday,

P

I’m of your father’s generation, but I too often feel “an odd proximity to the vanished past,” for me 1950’s Bensonhurst( some said “Gravesend” because we were on the border and it was a point of consideration contention), and the summers in the borsht Belt. I only met your paternal grandmother once, at your wedding, but she would have loved this piece. best wishes always, carole.