News Jews Can Use

My great-grandmother relied on the Jewish press. Now I do, too

For two years, I’ve been combing through Jewish arcana as I work on a reported memoir about the generational implications of policy, trauma and joy. Part of the story is told from my great-grandmother Eva’s perspective. But the further I got in my research, the more I worried I’d never be able to conjure Eva’s world. It seemed so foreign, immigrant-y and Jewish.

In the early 1900s, Jews in the Russian Empire were confined to the Pale of Settlement. The State and Church actively encouraged random acts of rape and murder, and the Czar’s army conscripted Jewish boys as young as nine. Worse, revolution was in the air. Revolution doesn’t usually work out well for a nation’s Jews. The Jews who could leave did. In 1902, teenaged Eva left the Russian Empire — her family’s home for over a century — to build a new life in the United States.

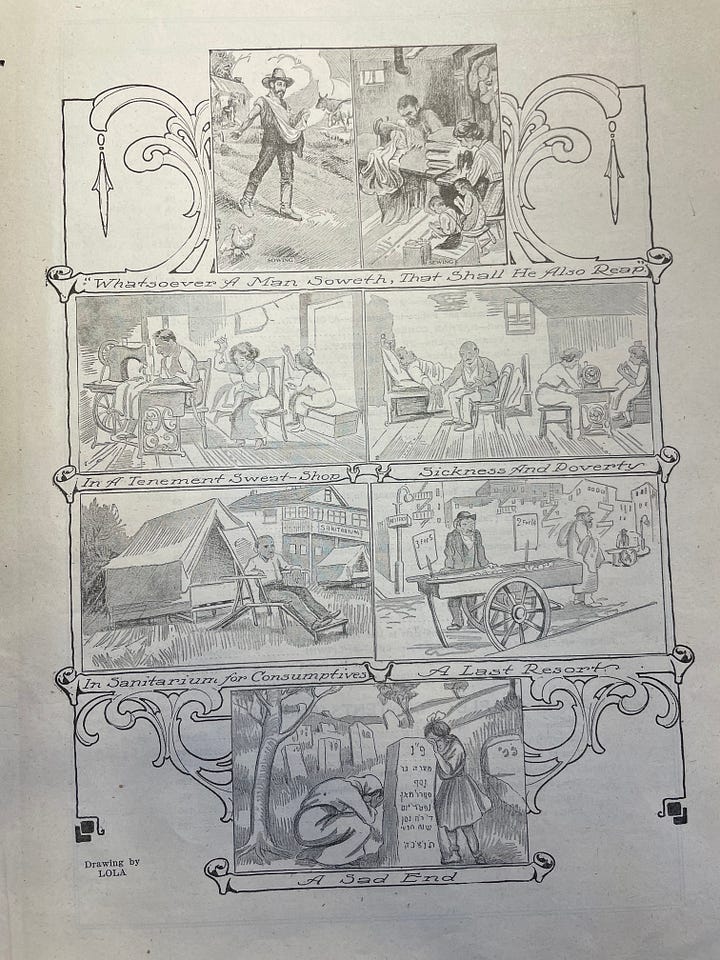

Along with 1.5 million Jewish refugees, Eva made her way to New York City, where supposedly antisemitism was nonexistent, and full-fledged citizenship was possible. Soon, 700 Jews per acre packed the Lower East Side, stuffed into tenements with no running water. Medical care was inaccessible, unless you wanted a nurse to save your soul before tending to your ailments. Tuberculosis ran rampant, passing from one coughing sewing machine operator to another.

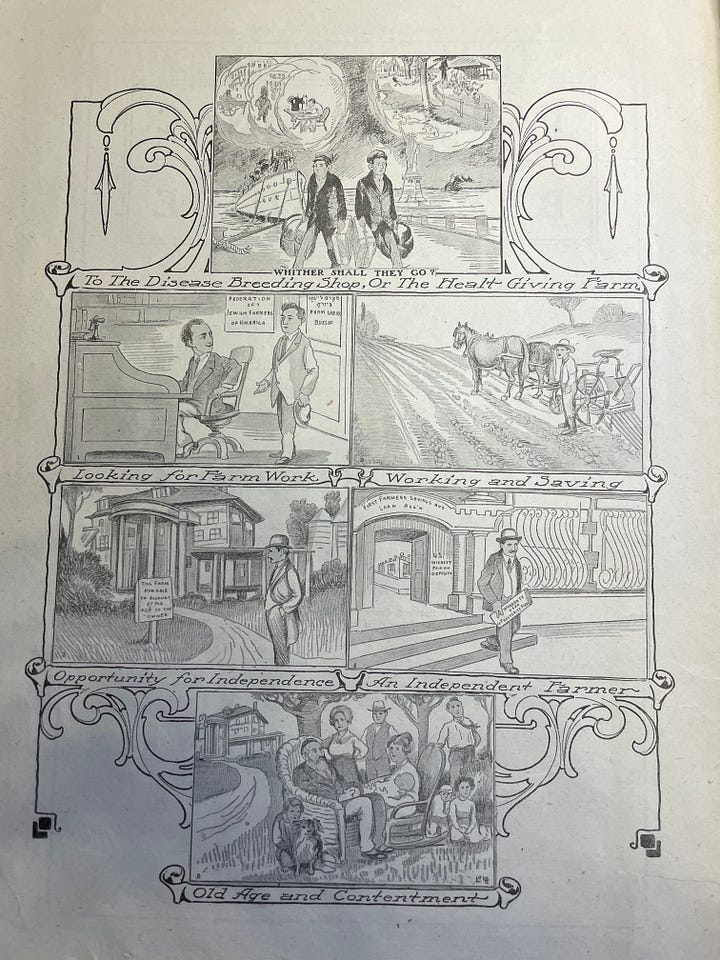

Philanthropists Baron de Hirsch and Jacob Schiff dreamed of a better life for Jews fleeing the Russian Empire than the Lower East Side. Also, Russian Jews needed to stop being so filthy and poor — they were freaking out the normal New Yorkers. What if, instead of wallowing in disease-infested drek and churning out shmattes, Jews turned the rocky Catskill Mountains into a Jewish agricultural paradise? Or the swampy parts of New Jersey? Or the really WASP-y parts of Connecticut? Eva and my great-grandfather Abraham were two of thousands of Jews who bought into this plan.

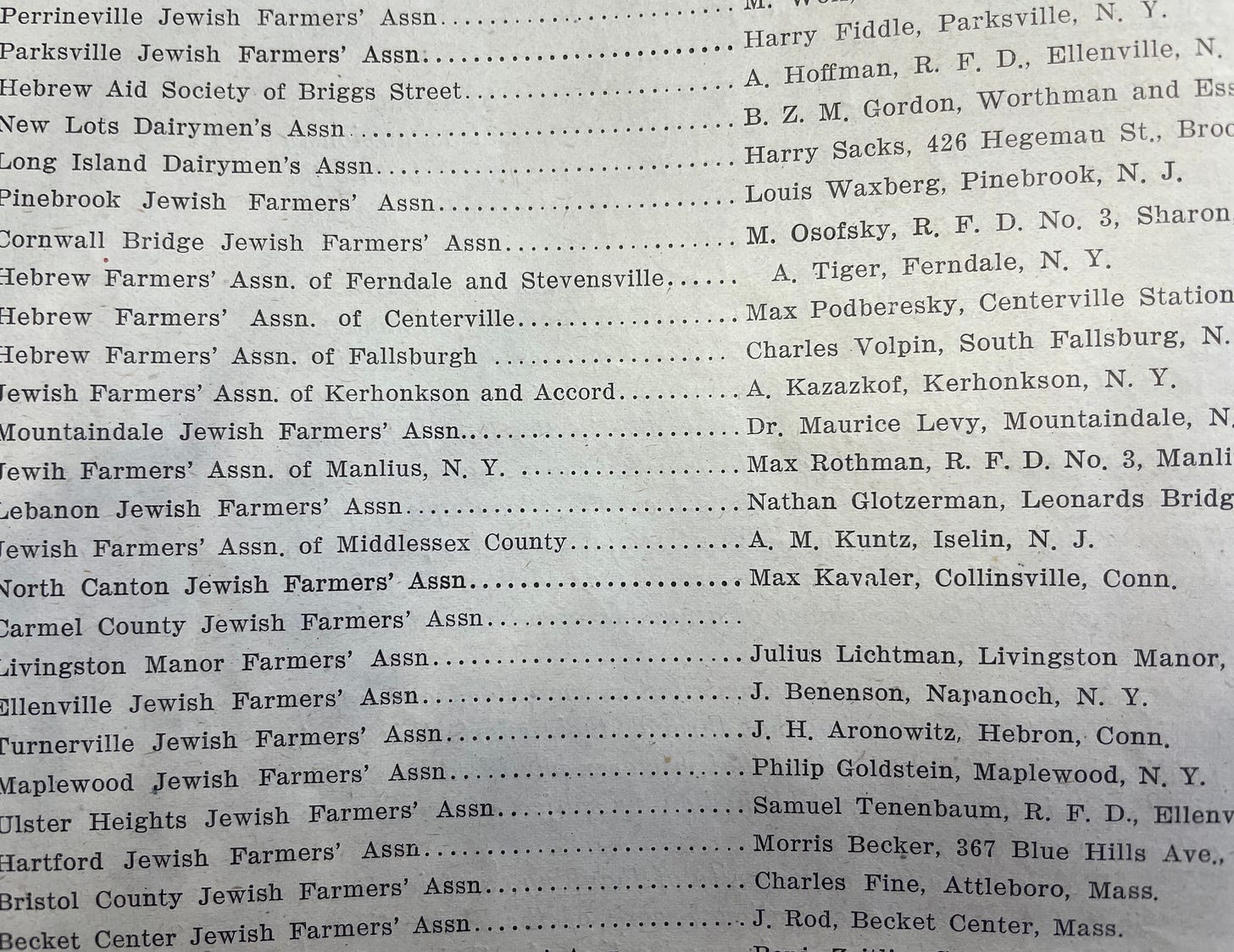

With help from de Hirsch and Schiff, the Federation of Jewish Farmers came into being. For over a decade the Federation published magazines, seed catalogs, and almanacs for Jewish farmers trying to grow crops on less-than favorable soil. Even pig raising was encouraged, to help one’s fellow Americans. (No eating the pigs, obvi.)

As I clicked through a vanished world, the remote Jewish enclave in Yah-Chupetz-Ville grew more distant. Jewish farmers in America? This America?

What was it like to grow up in a country where Jewish life was so restrictive and violent that your best option was to steamship it into the unknown, alone and broke, at 16? To read antisemitic headlines in the Catskills papers decrying the influx of Yiddish-speaking “Hebrews?” To be told the United States was open to Jews, then see hotels and entire towns boasting “No Hebrews Allowed?” How, I worried, would I ever bring this strange world to life?

I don’t worry any more.

I know what it’s like when Jews are murdered an ocean away. The horror of tremors in the Jewish Universe. The twitch. Feeling as though you personally were raped, your children butchered, your husband nailed to the floor, then dismembered. I’ve felt the rising terror, the unstoppable tears, the terrible realization that Jewish life in my country may be temporary, that my home could become another footnote on a tour of Capitals of Yesteryear — here is where the Jews lived, isn’t it so cute and medieval, but they don’t live here any more. They left! One fine day they just got up and left, that’s what happened.

Eva’s news came exclusively from Jewish news outlets. She not only read the Jewish press, she wrote ads for the family’s Kosher-ish hotel in the winter resort of Lakewood, New Jersey. (After they nearly starved to death in the Catskills, Eva and Abraham gave up farming and headed south. To New Jersey.)

My understanding of the Jewish press in the United States was that as Jews gained fluency in English and assimilated, they no longer need their own papers. Now I know it’s not about the language. It’s what the newspaper covers and how they cover it.

I had no need for a Jewish press until I was scrambling to evacuate my son from Tel Aviv after the attack and discovered — to my astonishment — the American papers did not have the news I needed. The American coverage did not include that an IDF soldier was disciplined for planting a tree in Gaza, or violence at the Free Palestine protest in Times Square. No one covered the screaming in the Knesset from a right wing and a left wing whose blood runs through my veins. Hysterical screaming was what I needed.

I hunted around for Jewish voices discussing Jewish problems, and found the Jewish Broadcasting Network. I turned on a rabbi round table and left it on all day, the Jewish intonations, the arguing, the candid back-and-forth a cooling balm on my shredded heart.

Then, the American papers started running the opposite of the news I needed, turning starkly antisemitic long before Israel responded. How had I, a journalist, missed the story the New York Times, the Washington Post and NPR had been telling for years about Jews and Israel? I watched with horror as outlets I considered my home cherry-picked misrepresentations to fit their narrative of Israel Bad and Jewish Death Not Newsworthy.

The news Eva needed wasn’t in the papers either. No one believed deep depravity was possible from upstanding German citizens. The first time the New York Times covered the Holocaust was June 27, 1942. At the bottom of page 5. Below a story about someone getting hit with a frying pan.

Today, Jews are once again the recipients of barbarous acts no one can comprehend, facing an enemy whose long-range goal is erasing the Jewish people. We have always lived with hate. But now, my family has been American for over 120 years. We’ve assimilated and integrated. We thought we were a part of American society. The Jewish press today is different than it was in Eva’s day, but it’s been there all along, waiting for me to realize that the American press has never treated Jews like other Americans.

For a year, I tried to reckon with the parallel and contradictory worlds of the American and Jewish presses. I gave up. My new world is more like Eva’s — more Jewish, but more isolated. Since moving to Jewish Press World, it’s become harder to communicate with those living in American Press World. Eva’s friends were all Jews, because what was she going to talk to goyim about? They lived in a different, privileged world free from hate and murder. They didn’t worry someone might tear a mezuzah off the door frame or bomb their church on Christmas. They didn’t think about citizenship options or moving to a war zone. No one actively hated them or their people for a span of at least two thousand years, across continents and civilizations. Goyim didn’t understand Eva, and Eva didn’t understand them.

I suspect she didn’t see the point. Every Christmas, Eva left her Jewish world to sit near an indoor tree with her mechuteneste. Her son’s father-in-law was the president of CUNY, and probably a good guy.

But Eva didn’t care what ferkakte university he presided over. She winkingly referred to Dr. Mead as the “old man” to emphasize the vast ethnic and cultural divide. Numerically, she was older. But Eva knew the importance of laughter, music, and raucous holiday meals. She’d known Jewish terror and death, but craved Jewish joy. On Christmas, she clocked hours in a non-Jewish house, but couldn’t wait to get back to her hotel. Her Jewish hotel, where she could gamble, smoke, eat schmaltz and gribenes and be as loud and Jewish as she pleased.

There are fewer Jewish spaces to retreat to these days. The Jewish American press is old, the organizations created to help Jewish refugees no longer Jewish. But Jews want and need to connect. We need information, a space to cry, and a break from explaining antisemitism to our friends, neighbors, former colleagues, and Western morons appropriating Palestinian hate symbols as clothing.

It’s not the way I would have planned it, but today I am close enough to Eva’s world to write from her perspective. As antisemitism engulfs my world, I feel closer than I thought possible to my great-grandmother, who grabbed joy and pleasure where she could.

When Kennedy was President, and Jews thought the worst was behind them, Eva had a thing for JFK.

“He can park his loafers under my bed anytime,” she liked to joke.

This image — of Boston royalty fancying my loud, funny, Yiddish-accented great-grandmother — was hilarious to everyone, including Eva. Her joke was a comment about JFK’s looks, but also about Eva’s own status in America. JFK was fancy. Eva, a Russian Jew, was the opposite of fancy. Both existed in America, but they inhabited entirely different worlds.

And now, so do I.

I love reading your essays, thank you. What Jewish news outlets do you read?

Your writing is very compelling. I am not Jewish, but as a boy my mother’s best friend was Miriam Marx Allan, the daughter of Groucho Marx. We spent many happy hours with them at Groucho’s home, dining and talking endlessly. Wonderful memories. I recall Groucho telling about making reservations at a hotel in New York years before (I am 73 now so that was many many years ago). Anyway, after exchanging telegrams with the Grand Hotel the hotel’s contact finished with a one line t-gram with the words “Trust you are gentile”. The dining table fell silent in shock. I was soon ushered to a bed 🛌 I assume, to get the child out of the room. But it was too late. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I still think about that day/night and close my eyes and pray. How can people be so stupid and cruel? Some things never leave you. I lost my wide eyed wonder. I am still scarred that our friends could live in a place where that kind of thing happened. How could the brothers go on doing what they accomplished in a place where they knew that they were set aside from the rewards they were due? Stupid, stupid people. (sigh…)